Imagine Emily Dickinson not as an Amherst resident but as a settler of the American Midwest: the lyricism and vision of Comfort confirm Heady as an astute reader of human experience and transmitter of an understanding deeper than one encounters in typical histories or chronicles. ChengĬomfort is a taut poetic synthesis of female embodiment in history. Combining women’s journals of the 1910s and 1920s with testimonials about Great Plains agriculture, Sarah Heady seeks through found and invented language to harmonize these lived realities (and fictions) with the artifacts of local custom and lore.

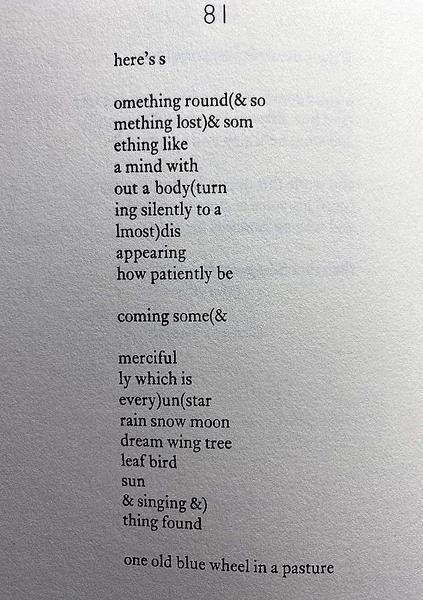

Drawing compellingly on found text and histories of rural America, Heady casts a rapturous spell dug up from the past, conjuring formidable incantations of the everyday: “scratching along the riverbed for finds.roaming the pomological fair, pressing into the tecting a thickness to the season.” In this way, Comfort keeps time according to the cadence of the hours while also letting it loose, surprising the reader with an intimate, strange, and epic vision that makes its way by “scattering night across the floor of the house” and casting “projections across the plain.” Jennifer S. What shapes of wildness and fecundity does a woman cultivate in the plot of world available to her? What home does she un/ravel for herself in the overlooked places of the house? In Comfort, Sarah Heady dares to uncover a poetics of domesticity that is vibrant with sensuality, texture, and mystery-where the mundane life of details becomes a world pulsing with pleasures, dangers, and questions of embodiment and the deep interior.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)